- Living

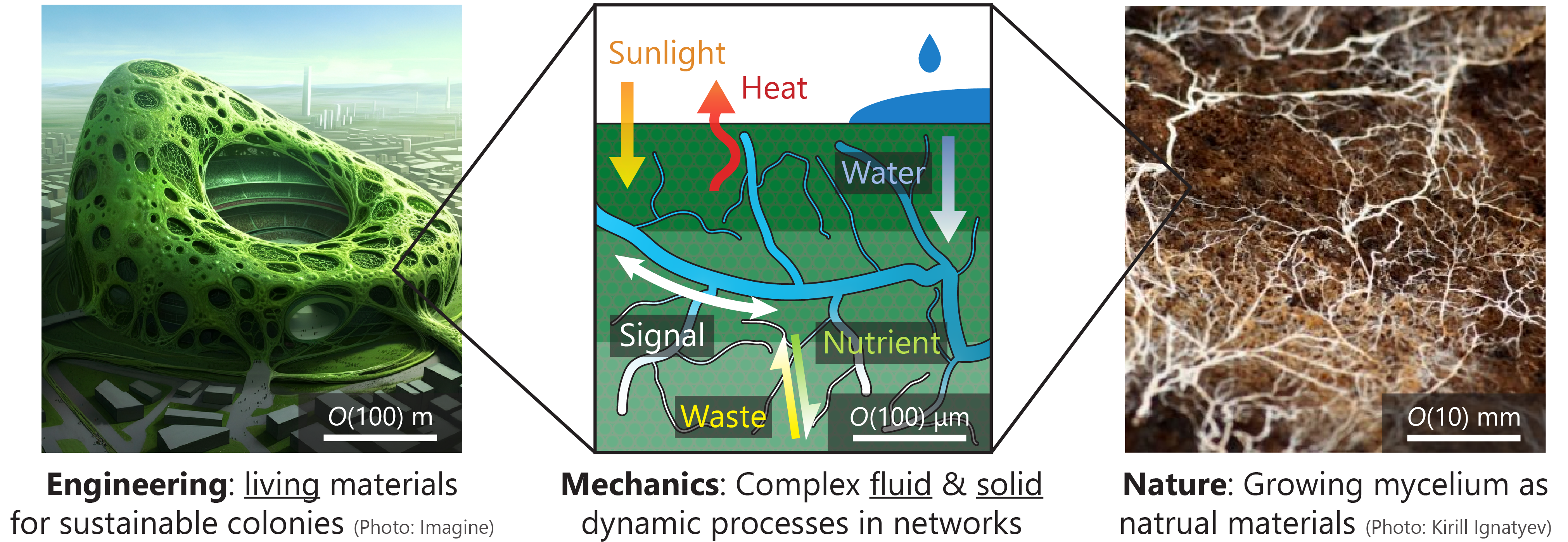

Living systems hold immense promise, inspiring engineers to create the next generation of sustainable, intelligent, and active materials. Separately, the growth and function of organisms as natural materials present fascinating fundamental physical questions. Mechanics play a critical role in both contexts.

As the Laboratory of Interfaces, Fracture, and Transport (LIFT), we aim to understand and explore the mechanics governing diverse systems, including living ones, primarily through experiments combined with mathematical modeling. We see a powerful synergy: studying these systems offers exciting new fundamental questions for mechanics, while a deeper mechanical understanding will enable the rational design of advanced materials with enhanced functionality, particularly towards sustainability.

In the sections below, we highlight some research directions rooted in fundamental mechanics. While our current interest extends towards living systems, these examples showcase the types of problems we tackle at the intersection of Interfaces, Fracture, and Transport. Our work is inherently interdisciplinary, and most projects bridge multiple fields!

- Interfaces

Draining Films and Self-Similarity

Liquid interfaces are everywhere, and thin liquid films often display rich physics. We study how a liquid film drains under gravity, a process critical in many industrial applications. Using interferometry, we can map the shape of the film with a precision of tens of nanometers.

For example, near a vertical edge, we observe that the draining film develops a complex 3D shape that evolves over time. Remarkably, we find this shape follows a special self-similar structure. This allows us to simplify the complex mathematical description, a Partial Differential Equation (PDE) with three independent variables, into a much simpler Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE). This connection links the fluid dynamics to fundamental concepts in applied mathematics. [Read our paper on Physical Review Letters]

We also explore the dynamics, similarity features, and instabilities of thin films in various other geometries. The interferometry patterns keep fascinating us!

- Fracture

Elastomers Fail from the Edge

How do soft materials break? For stiff materials like glass or metals, the process is well-established: cracks often initiate and propagate from within. However, for highly stretchable elastomers (rubbers), we have discovered a distinctly different failure mechanism: elastomers fail from the edge!

Using our customized imaging, we visualize the 3D fracture process in elastomers. Unlike the classic picture, failure begins with separate "edge cracks" forming at the sides of the sample. These cracks then propagate toward the center. The ultimate strength and toughness depend on how far these edge cracks must travel before meeting. Our results offer clear strategies for toughening elastomers by engineering their geometry, enhancing the durability of soft devices. [Read our paper on Physical Review X]

Interestingly, despite the absence of liquid, this 3D fracture also exhibits a unique self-similarity, connecting concepts in fluid mechanics and applied mathematics!

- Transport

Laboratory Layered Latte

Ever notice distinct layers forming when pouring hot espresso into warm milk? This intriguing pattern, emerging minutes after pouring, is not just a coffee shop curiosity: it is a window into fluid mechanics!

We investigate this using particle image velocimetry and particle tracking velocimetry. Flow visualizations reveal distinct circulation flow cells and mixing within each layer, driven by double-diffusive convection – an instability caused by competing heat and salinity (concentration) gradients, typically observed and studied in oceanography. By identifying the critical pouring conditions, we demonstrate control over the layering and extend this single-step process to create layered soft materials with spatially varying properties. [Read our paper on Nature Communications]

The initial pouring itself creates a fascinating mixing flow known as a negative buoyancy fountain, also involving complex transport dynamics!